I’m Anu! I research, make, craft, code, and sometimes, hack things.

Ethnography of Open Street Mapping 🤳

Here I will discuss an account of ‘street level mapping’ as case of community practice enabled by data-driven technology. The motivation for choosing street-level mapping is that it comes with an ethical undertone, as something inherently done for bettering society. At the same time, open source maps run by voluntary community effort show that it is possible to compete against corporate giants in destabilising their dominant influence on geographical mapping. The platform Open Street Maps (OSM), for example, acts as a powerful tool for emphasising ground truth in a way that empowers people by giving them the freedom to map places, businesses or roads on their own terms.

Image: The exact same location as depicted in Google Maps and Mapillary

In the study, I inquired into an open source mapping service in Sweden that supports a large community of mappers participating in their effort to create the ‘best’ photo-representation of the world. As an alternative case of mapping, my aim was to unpack not only the underlying motivations behind the service but also the community-drive for the practice. The service consists of a web platform and a custom smartphone application that offers an easy-to-use interface to capture, upload and edit street-level photos.

Its most striking feature is the automatic-capture mode that takes photos every few seconds, making it possible to map territories by simply mounting the smartphone on a vehicle and letting the application run without requiring any human intervention. Computer vision techniques are then used to stitch the photos to create visually stable street-level maps. The service further employs object-recognition algorithms for identifying public objects like streetlights and traffic-signs, which are relayed to governments and private enterprises for their own uses. In this sense, the service’s focus lies in their use of computation for street-level mapping as well as in offering visual analytics as a service. In such a data driven model, the ethics of maintaining privacy and integrity of subjects in the photos is mostly left to the mapper’s moral judgment. As such, the service relies on general ethical guidelines suggesting that mappers should avoid sensitive content like capturing people’s faces or vehicle

license plates in photos.

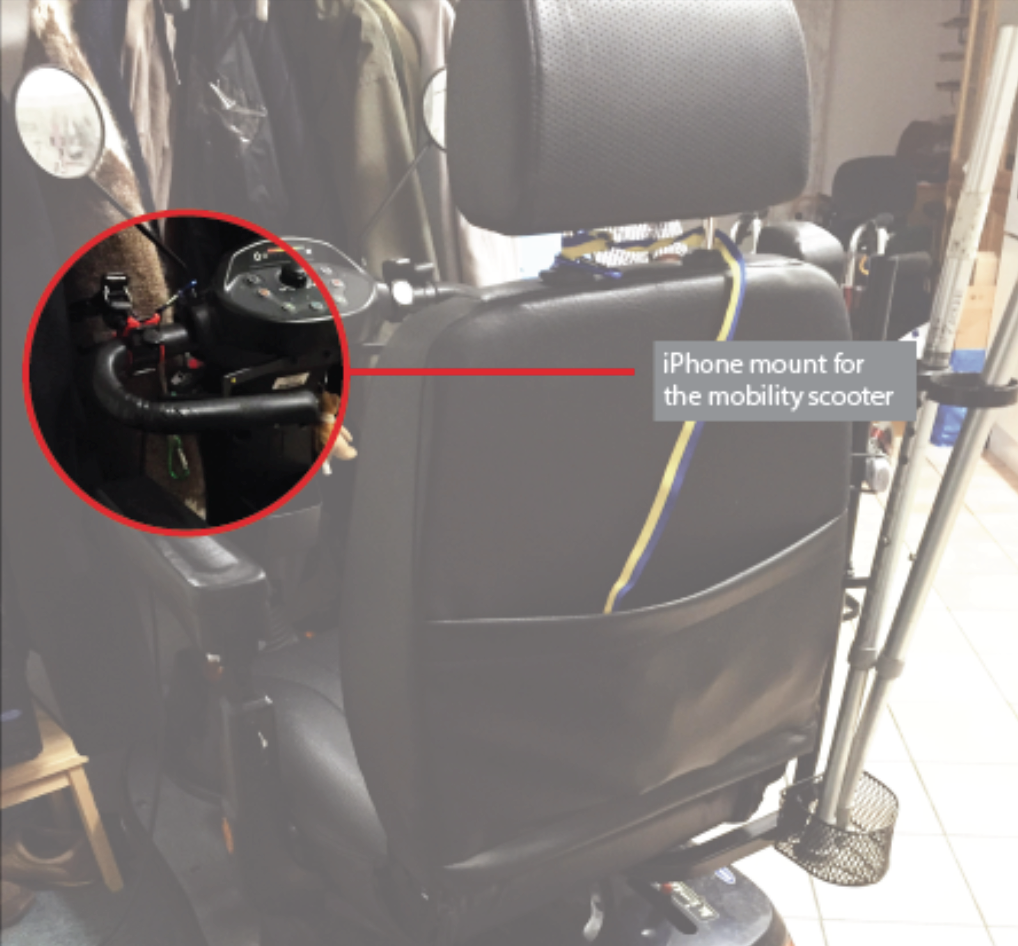

I contend that inquiring into how mapping comes about in the daily habits and activities of mappers might help negotiate the ethics concerning neutrality and privacy in street-level mapping. By conducting interviews with mappers from the mapping community, I discovered that most of them liked to map in their spare time – while returning from work or on weekends and holidays when they may afford to go on long drives and walks. This includes the time and care that they dedicate to fixing a car or bicycle mount for mapping or pre-planning an extensive route to map specific areas and not others. As such, this preparation activity came across as an integral part of the process of mapping as it gave the mappers a feeling of ownership of the practice. An evidence of this feeling was brought to light in an interview with a differently-abled mapper from the community.

As seen in image below, the mapper fashioned his own iPhone mount to fit on top of his mobility scooter, which he said brought him immense satisfaction in trying out different arrangements until he found one that was conducive for mapping. He further discussed how he enjoys tuning and repairing the arrangement to get the right angle, level and balance before going out to map. From here, I derived the insight that the ritual activity of ‘setting-up’ before mapping is strongly linked to the way mapping takes place. In that, it showed the potential for design to intervene in the activity by giving mappers the means to spend that time negotiating how they wish to map in the most ethical way possible.

At the same time, street-level mapping has gathered attention from people who travel for leisure – bloggers, adventurists, and mappers. Besides the obvious motivation to contribute to mapping through one’s travels, street-level mapping also ties into other relations. For example, a community-mapper and his son recently mapped the Faroe Islands in response to Faroe Islands’ petition to bring Google Street View to the island. Not only was their trip motivated by the desire to be the first street-level mappers on the island but they also shared the affective quality of bonding between the father and son. Another instance of bonding was evident from an interview with community’s mappers in India. One of the members discussed how she always asked a friend to accompany her when she went out mapping. In that, she claimed to enjoy her friend’s company in discovering new places, engaging in occasional chitchat and receiving spontaneous suggestions for where to map next. It meant that both of them trust and respect each other’s contribution to the shared activity. How can mapping become a part of this exchange?

Furthermore, the company's mission to capture the ‘best’ photo-representation of the world ties directly into the way open source map data deals with the problem of neutrality. As one mapper exclaimed, “I like to use image sequences to map churches in small villages because I want them preserved for future generations.” To a large extent, it is difficult to classify this kind of mapping as a neutral contribution. As more and more of such contributions pour in, the map becomes a large repository of street-level photos with rich subjective data that might go unnoticed by whom the mapper intends to map for. Besides, open source map data is always at the risk of deletion or vandalism, and the only way of securing that data is by making copies and storing them in a safe location. In this regard, I drew the insight that there is a need to support subjective contributions of map data in addition to the need of securing that data so it does not get lost.

I combine these insights into design concepts as a way of demonstrating opportunities for supporting ethics in street-level mapping. Each concept is briefly explained without going into too much detail about its inner workings.

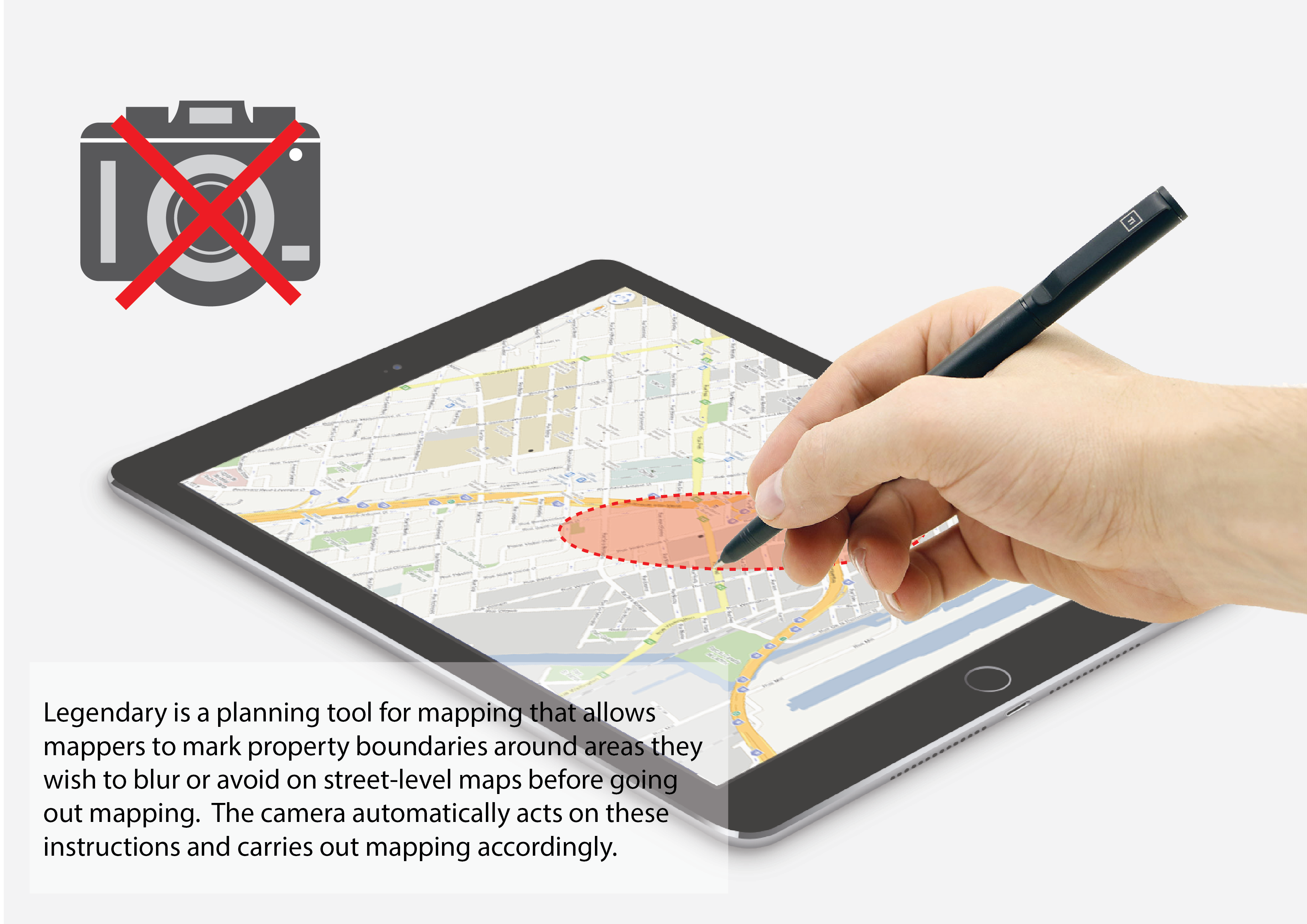

Legendary

Legendary is a pre-planning tool that allows mappers to mark property boundaries that they wish to blur or avoid on street-level maps before going out mapping, such as plots of land, buildings, crowded streets or parking areas. The application picks up on the location coordinates of those boundaries and sends them to the camera automatically. The camera acts on these instructions and carries out mapping accordingly.

GPS Radio

GPS Radio is a device that allows a person to stream street-level data from a car to any location around the world by tuning the device to that specific destination. A person would be able to stream data to a friend or family member living in another part of the world, but someone living in the same location will be allowed to access the stream openly. The stream is short-lived and self-deleting once the mapping stops.

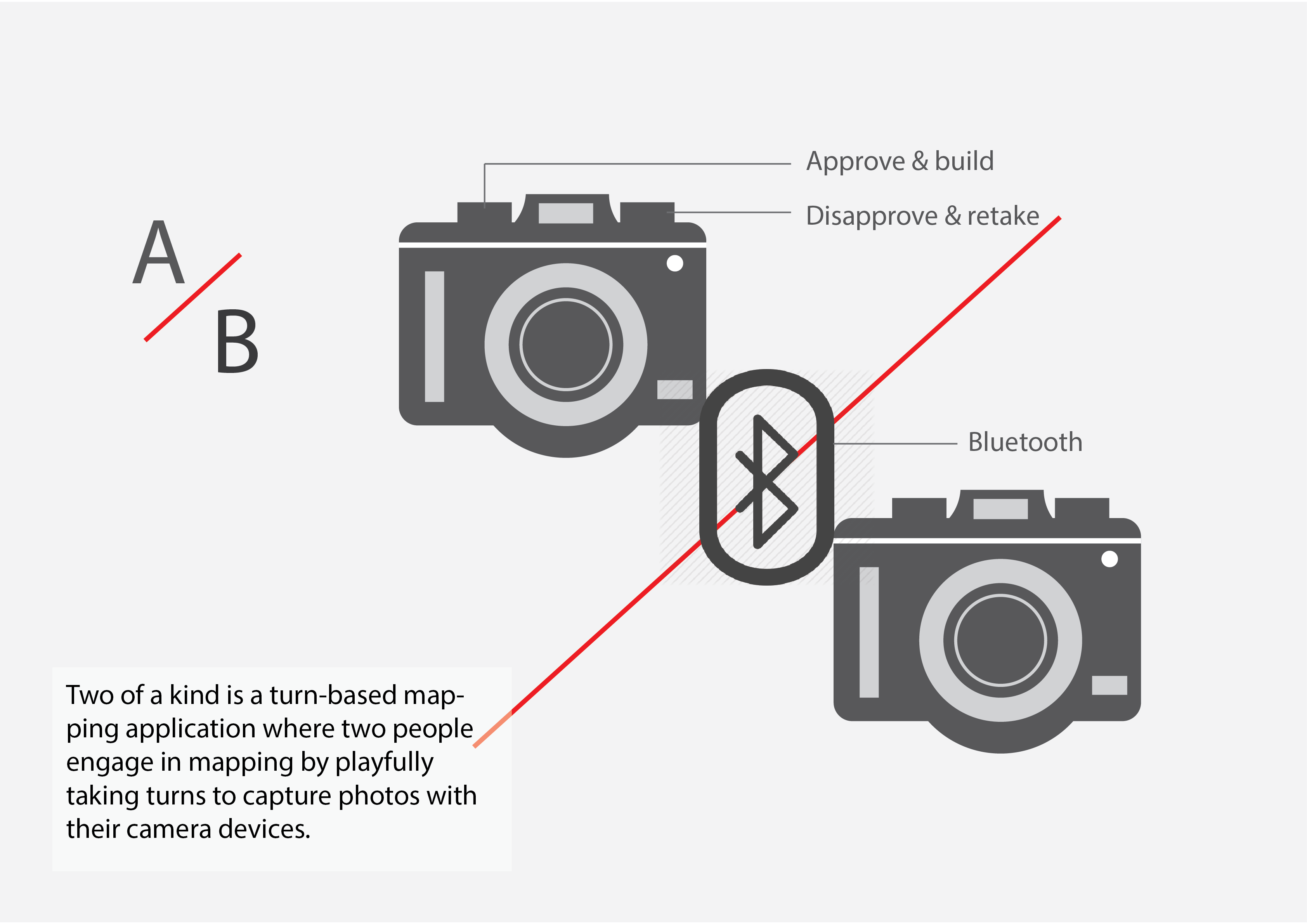

Two of a Kind

Two of a kind is a turn-based mapping application where two people engage in mapping by playfully taking turns to capture photos with their camera devices. When one person captures a photo, the second person receives it. She responds to it by either approving the photo and capturing a new one or she disapproves the photo and retakes the same photo in different way, which goes back to first person and so on. As the cameras are connected, both persons are required to stay within close proximity of each other for the application to work.

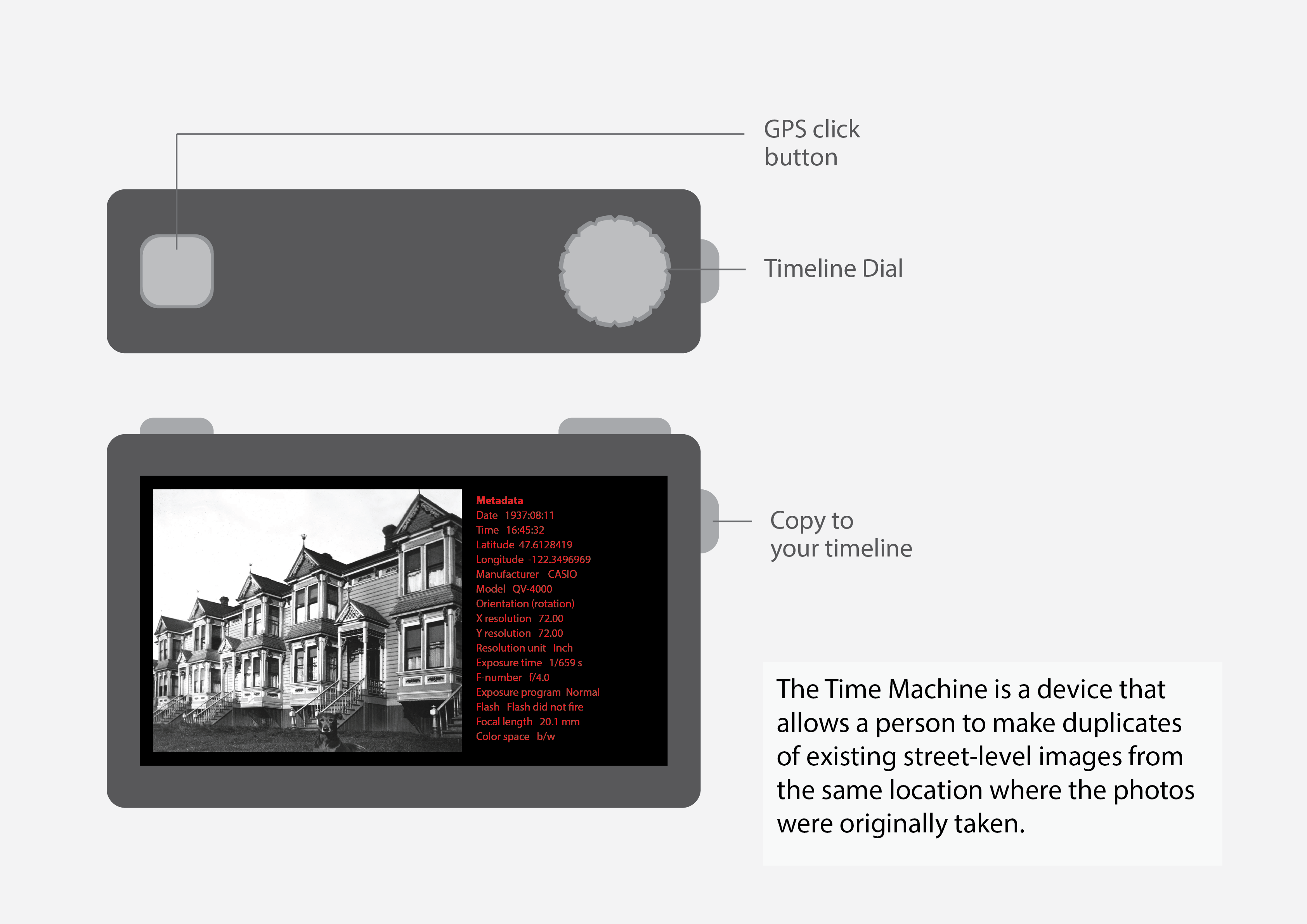

Time Machine

The Time Machine is a device that allows a person to make copies of existing street-level images from the same location where the photos were originally taken. The Time Machine is particularly suitable for walking around a city and engaging with location-based archives of street-level imagery. The person is allowed to make copies of those images if she wishes to protect them from being vandalized.

Discussion: Recognizing potential for ethical reframing

Basing a part of the study on ‘an ecology of practices,’

street-level mapping was examined not as a standalone practice but as a part of a mapper’s daily habits and activities. In that regard, Legendary focuses on the activity of setting up for mapping as it shows potential in the way mappers dedicate care and attention to the set up process before mapping. By leveraging on this potential, there was a possibility to explore how mappers may engage with setting up for privacy as a part of that activity. Similarly, Two of a kind reframes mapping as a bonding activity by drawing on the potential for ethics in the bond shared between the two participants in the activity. In this way, I contend that activities and habits of practices may be examined for potential in dealing with ethical challenges. The implication for design lies in developing approaches to recognize that potential for reframing to support ethics in practices.

Ethical positioning

Marres (2011) argues that materials in practices may participate in enabling an ethical positioning in relation to issues of concern. In that sense, the GPS Radio reveals the way in which streaming street-level data to a specific destination allows the device to participate in the issues of neutrality in open source mapping – who receives my data, where is it going, and how is it being used? Similarly, the Time Machine highlights how timestamps and location data may participate in supporting the maintenance of the map against vandalism. In this sense, material participation calls attention to the way in which exploring the capacities of different materials in practices allow new possibilities for ethical positioning to unfold. The consequence for design, however, is that there is no way to know when a design is good enough. As such, the experimental and exploratory character of this approach makes it necessary to complement it with the other perspectives that are better grounded in their approach to ethics in practices.

Affective relations as guides for ethics

I have described how mapping ties into relations that are not just material but also affective. The concept Two of a kind relies on the social bond shared between two participants as they engage in street-level mapping. This bond has an affective quality that has the potential to guide how ethics is carried out in practices. In that, affective relations involve a range of human sensitivities that may be accommodated in the practice, such as being slow or spontaneous, careful or rash, silly or serious, while still being respectful to one another. In this respect, affective relations may act as guides for supporting ethics in practices. At the same time, there is a need for more methods in design that are especially tailored to the exploration of affective relations in practices.

Author Note

This text consists of excerpts from a paper titled 'Design as an Ethics in Practice.' The original paper may be accessed upon request if anyone wishes to read the elaborated version of this text.

References

Mantelero, A. 2016.Personal data for decisional purposes in the age of analytics: From an individual to a collective dimension of data protection. Computer law & security review, 32(2), pp.238-255.

Stengers, I., 2013. Introductory notes on an ecology of practices. Cultural Studies Review, 11(1), pp.183-196.

Sweden, M.A., n.d. Manifesto [WWW Document]. Mapillary. URL https://www.mapillary.com/ (accessed 4.1.17).